Distinguishing PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Borderline Personality Disorder using Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling

Highlights

- Exploratory SEM was used to identify overlap between complex PTSD and BPD

- Distinguishing features of ICD-11 complex PTSD and BPD were found in urban sample

- There was more overlap between BPD and complex PTSD when using DSM-5 PTSD symptoms

- Consideration of the diagnostic structure of PTSD used is critical

-

The "Winning" Model: A three-factor model (ICD-11 PTSD, DSO, and BPD) fit the data best, proving they are distinct constructs.

-

The Divider: Trauma-related avoidance was a primary differentiator for CPTSD, while aggressive behavior was more characteristic of BPD.

-

The System Matters: When using DSM-5 PTSD criteria, the lines between DSO and BPD became blurred, suggesting that ICD-11 is more effective at separating these diagnoses.

Abstract

There is debate about the validity of the complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) diagnosis and whether disturbances in self-organization (DSO) in CPTSD can be differentiated from borderline personality disorder (BPD). How PTSD is defined may matter. The present study used exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) to replicate and extend prior work by including two models to examine how PTSD (ICD-11, DSM-5), DSO, and BPD symptoms relate. Participants (N = 470; 98.1% women; 97.7% Black) were recruited from medical clinics within an urban hospital. PTSD, CPTSD, and BPD were assessed using semi-structured interviews and trauma-related avoidance, aggressive behavior, and anxious attachment were assessed using self-report measures. ESEM models of PTSD, DSO, and BPD symptoms were run. We found a three-factor ESEM model of CPTSD (ICD-11 PTSD and DSO symptoms) and BPD symptoms best fit the data and found support for discriminant validity between factors across trauma-related avoidance, aggressive behavior, and anxious attachment. For DSM-5 PTSD, a two-factor ESEM model was best-fitting (PTSD and DSO/BPD). The findings demonstrate clear distinguishing and overlapping features of ICD-11 PTSD, CPTSD, and BPD and the necessity to consider the diagnostic structure of PTSD in determining the additive value of CPTSD as a distinct construct.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 3072) were recruited from waiting rooms in primary care, gynecology and obstetrics, and diabetes medical clinics at a publicly funded, safety-net hospital in the southeast region of the United States as part of an ongoing study of risk and resiliency to the development of PTSD in a medical care seeking population (Gluck et al., 2021). Data for the present study was collected between February 2014 and September 2019. Interviewers approached anyone in the waiting room and did not restrict who to approach based on certain characteristics. Inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 65 and capacity to provide informed consent. The investigation was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent of the participants was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been explained.

A subgroup of participants (N = 484) was contacted to return to our laboratory for a separate, but related study. These participants were given structured clinical interviews and additional self-report measures (approximately two weeks post-initial assessment). Participants were offered the opportunity to participate in this clinical assessment portion based on eligibility for other ongoing studies in the lab, including studies on risk and resilience for PTSD, intergenerational trauma in mothers and children, and comorbidities between physical health and psychiatric problems. This portion was conducted by interviewers with additional training in administering structured clinical interviews and who were supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist on staff. Participants were paid $60.00 if they returned to complete this phase of the study. Participants were included in the present analysis if they were administered the semi-structured DSM-5 PTSD assessment (described below), resulting in a final sample of 470.

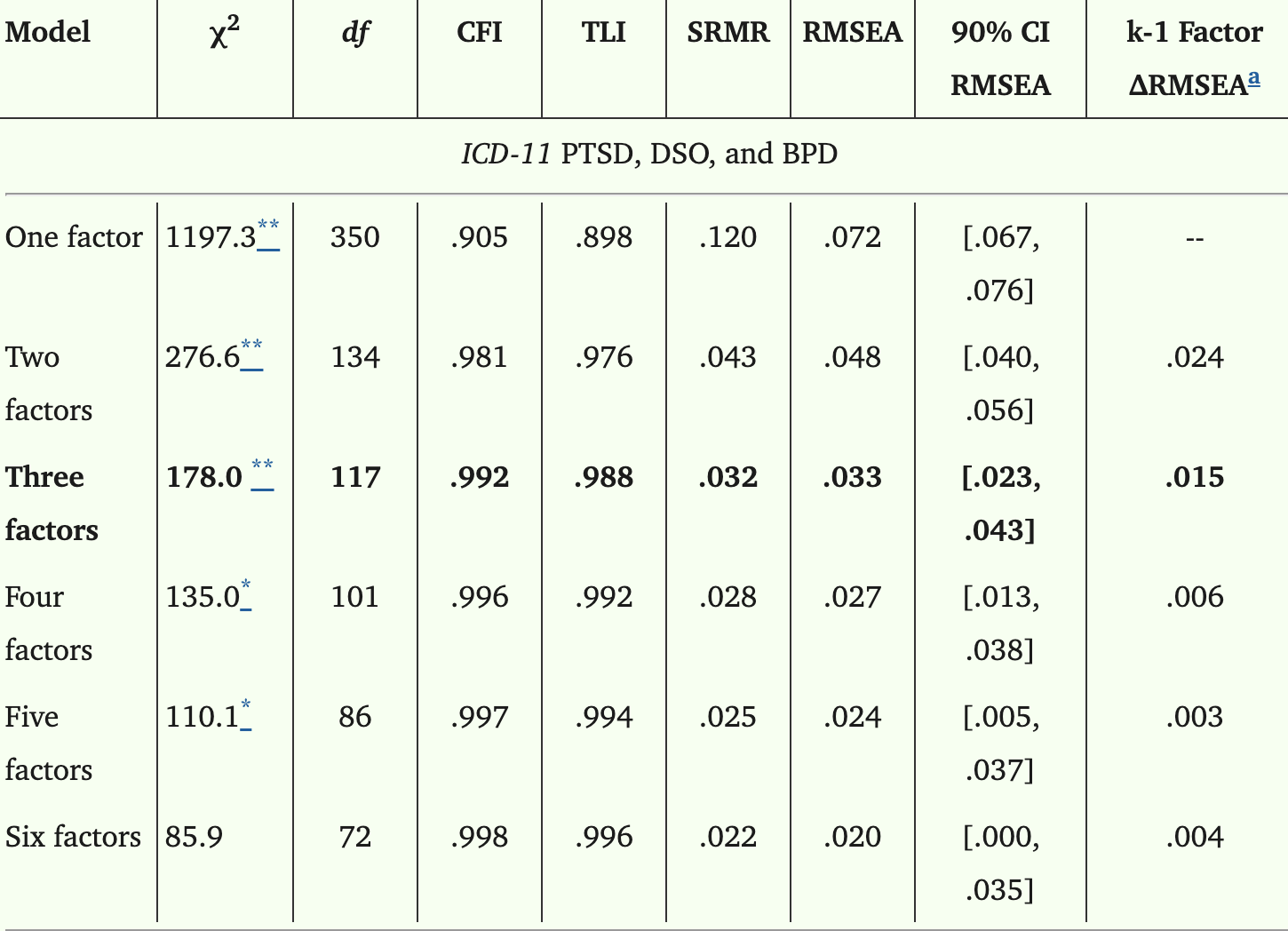

Model

First, we tested one- to six-factor ESEM solutions and determined the optional number of latent variables needed to explain the covariation between the 6 ICD-PTSD, 4 DSO, and 9 BPD symptoms. For the purposes of creating an ICD-11 PTSD latent variable, we used DSM-5 measures to approximate the ICD-11 criteria (e.g., selecting symptoms B2, B3, C1, C2, E3, and E4 from the CAPS-5). Then, we re-tested one- to six-factor ESEM solutions with the inclusion of all 20 DSM-5 PTSD symptoms, 4 DSO, and 9 BPD symptoms.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings support the distinct constructs of PTSD, DSO, and BPD when using ICD-11 PTSD criteria but not when using DSM-5 PTSD criteria, demonstrating that how PTSD is defined matters significantly when considering the construct of CPTSD and its value as a distinct diagnosis. Regardless of the diagnoses that are used, determining the constellation of symptoms present for an individual patient and incorporating that into one’s treatment plan is key. Clear overlap between PTSD, DSO, and BPD symptoms exist and consideration of trauma-informed treatments that may address underlying transdiagnostic symptoms like emotion dysregulation (e.g., Dialectical Behavior Therapy or DBT; (Linehan, 2020)) in individuals exhibiting symptoms of DSO and/or BPD in the context of PTSD is warranted. At this time, there is not clear evidence that certain types of trauma-focused treatments are superior to others for individuals with DSO/BPD symptoms or whether phased-based treatments are necessary. Thus, continued research is needed into how symptom presentation across these varied diagnoses may impact trauma-focused treatment choice. We also found that the DSM-5 PTSD factor included the six core symptoms of PTSD from ICD-11 but also included additional ones, suggesting more research is necessary to understand how these differing PTSD definitions relate and what PTSD symptoms may be most critical to the diagnosis.

The model discussed in the sources is Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling (ESEM), a statistical technique used to identify how different psychological symptoms cluster together to form specific disorders.

How the Model Works

ESEM is a latent variable modelling technique uniquely designed to handle the overlap between similar conditions, such as Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Complex PTSD (CPTSD), and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). Unlike more traditional models that require symptoms to belong strictly to one category, ESEM allows for cross-factor loadings. This means the model acknowledges that certain symptoms (like "uncontrolled anger" or "paranoia") might naturally appear in more than one disorder at the same time.

By allowing these overlaps, the model provides a more accurate picture of how these conditions relate to one another without forcing them into "neat" but inaccurate boxes. The sources used this model to compare two different diagnostic systems:

• ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases): Using this narrower definition of PTSD, the ESEM model found three distinct factors: PTSD, Disturbances in Self-Organisation (DSO—the "complex" part of CPTSD), and BPD.

• DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual): Because this system uses a broader definition of PTSD that already includes many mood and cognition symptoms, the model found only two factors: PTSD and a combined DSO/BPD factor.

Example: Making a Differential Diagnosis

You can use the insights from this model to differentiate between CPTSD and BPD, which often look similar because they both involve difficulties with emotions and relationships.

If a patient presents with trauma-related distress, you can look for these distinguishing features identified by the model and its external correlates:

1. Examine the "Sense of Self"

• CPTSD: Look for a persistent negative sense of self (e.g., "I am worthless" or "I am broken").

• BPD: Look for an unstable sense of self that shifts between internalising (negative) and positive views.

2. Evaluate Relationship Patterns

• CPTSD: Relationships are typically marked by avoidance, disconnection, and a tendency to stay away from others. This is strongly associated with anxious attachment (preoccupation with others' affection or fear of abandonment).

• BPD: Relationships are more likely to be volatile and involve intense efforts to connect with others specifically to avoid being abandoned.

3. Assess Affective Regulation and Behaviour

• CPTSD: Emotional dysregulation often manifests as trauma-related avoidance (avoiding thoughts, feelings, or people associated with the event).

• BPD: Emotional dysregulation is more strongly associated with aggressive behaviour or extreme strategies like self-harm and suicidality to escape intolerable emotions.

Case Summary Table for Differential Diagnosis:

| Feature | CPTSD (ICD-11 PTSD + DSO) | Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sense of Self | Consistent and negative. | Unstable and fluctuating. |

| Relationships | Avoidant and disconnected. | Volatile with fear of abandonment. |

| Primary Driver | Trauma-related avoidance. | Interpersonal dysregulation/Aggression. |

| Attachment | High anxious attachment. | Variable; less uniquely tied to anxious attachment than DSO. |

To think of this model in a simpler way, imagine three different colours of ink—red (PTSD), yellow (DSO), and blue (BPD)—dropped onto a wet piece of paper. A traditional model tries to keep the drops separate, but ESEM acknowledges that they will naturally bleed into each other, creating orange or purple areas. By looking at where the colours remain "purest" (like the specific link between BPD and aggression), clinicians can identify the original "colour" or primary diagnosis of the patient's distress.

source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9107503/

#BPD #cPTSD #trauma #statistics #model #psychiatry #disorders